After graduating in 1994, I joined MCI as a Territory Account Executive, earning a base salary of $19,000 plus commissions. Tasked with cold calling businesses across central and southern Oregon—from Eugene to Ashland to Bend to the Oregon coast—I honed outreach and relationship-building techniques. Each morning, I organized prospects in my Franklin Planner and dialed lists on a touch tone phone. I soon discovered that rustic coastal hotels made ideal customers because they often “comped” me and my wife a room so I could demonstrate the service in person. At 23, a room in a hotel on the beach was no trivial matter, especially since it was a 4 hour drive back home to Eugene.

Those days of cold calling may seem archaic and quaint now—and not everyone would mourn them—but what’s replaced cold calling poses far greater challenges for small businesses and economic diversity.

Abstract: This article examines how asymmetrical regulation has privileged digital advertising platforms while strangling telemarketing, creating a market structure that systematically disadvantages small and medium businesses. Drawing on historical telemarketing data, digital advertising economics, and telecommunications regulatory analysis, I demonstrate that ostensibly consumer-protective measures have effectively concentrated market power in digital platforms. Whether by design or unintended consequence, this regulatory imbalance has erected formidable barriers to market entry, undermining entrepreneurial competition and reinforcing digital monopolies.

The Historical Evolution and Contemporary Decline of Telemarketing

Telephone-based direct marketing constituted a foundational channel for American business growth throughout the twentieth century. As early as 1908, New York’s Equitable Trust Company established a dedicated telephone bureau with 12 agents (Equitable Trust Annual Report, 1908). By the mid-1930s, firms like Midwest Steel Co. had developed sophisticated “inside sales” departments where agents worked through prospective client lists via switchboard trunk lines (Midwest Steel Co. Bulletin, 1936).

The first contemporary telemarketing operation emerged in 1957 when Time, Inc.’s Life Circulation Company established a dedicated call center in Manhattan for magazine subscription sales. According to Time, Inc.’s 1957 Annual Report, this operation began with five operators using Western Electric key telephone systems, with each agent averaging approximately 200 calls daily. This model established the blueprint for subsequent telemarketing enterprises (Time, Inc. Annual Report, 1957).

Telemarketing expanded rapidly across sectors. American Express’s outbound team generated nearly $10 million in new charges during its first year of operation (American Express Annual Report, 1965). By 1985, predictive-dialer systems manufactured by companies like Mitel pushed agent utilization rates above 60%—tripling contact rates—and reduced average customer acquisition costs to under $10 per customer, compared to $100 CPM for television advertising (Direct Marketing Association, 1986; DMA Cost Benchmark Report, 1988).

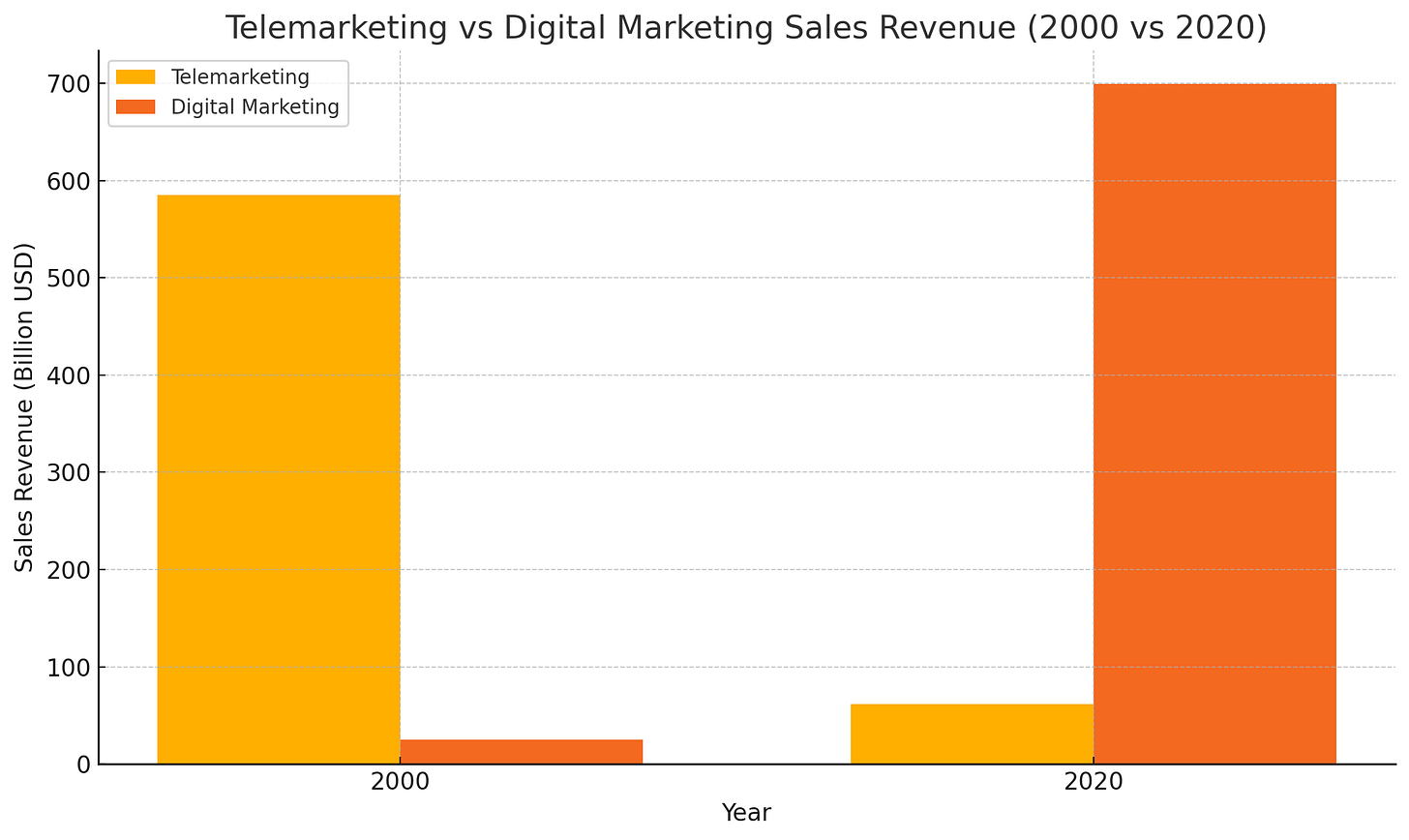

At its zenith in the year 2000, telephone marketing generated approximately $585 billion in U.S. sales, employing 5.6 million workers across 69,500 call centers (Ad Age, 2003). However, by 2020, telephone marketing expenditures had contracted to $61.4 billion (Statista, 2020), with the industry experiencing substantial decline following regulatory changes such as the National Do-Not-Call Registry implemented in 2003. This dramatic reduction indicates a substantial reallocation of marketing expenditure toward digital platforms, which grew to $526 billion globally by the end of 2024 (WordStream, 2025)—reflecting a fundamental transformation in how businesses reach potential customers.

From Cold Calls to Clicks: Comparing Telemarketing and Digital Marketing in 2000 vs. 2020

In 2000, telemarketing powered roughly $585 billion in U.S. sales, backed by 5.6 million call‑center employees across 69,500 centers (Ad Age, 2003). That same year, digital marketing was just getting started, with about $5 billion in ad spend delivering $25 billion in sales at an average 5:1 ROI (Demand Sage, 2025).

Fast forward to 2020: telemarketing revenue had dwindled to $61.4 billion, driven down by the National Do-Not-Call Registry (established 2003) and rising consumer controls (Statista, 2020; Federal Trade Commission, 2003). Offshoring shifted roughly 1.3–1.5 million jobs to the Philippines and another 1.1–1.3 million to India by 2023, yet the global telemarketing workforce still sits well under its U.S. peak, indicating many roles were permanently lost (Site Selection Group, 2023).

By comparison, digital marketing exploded: U.S. internet ad revenue climbed to $139.8 billion in 2020, generating an estimated $699 billion in sales at a 5:1 ROI (IAB/PwC Internet Advertising Revenue Report, FY 2020; Demand Sage, 2025). Advances in search, social media, and programmatic buying gave advertisers precise targeting and real‑time analytics, completely reshaping how businesses connect with customers.

This side‑by‑side look at 2000 and 2020 underscores the seismic shift from cold calls to clicks—and the migration of marketing dollars from traditional telemarketing to digital channels.

Digital Advertising’s Escalating Cost Structure and Market Concentration Effects

The contemporary digital advertising landscape presents formidable economic barriers for smaller market participants. When Google AdWords (now Google Ads) launched in 2000, the average cost-per-click was approximately $0.46 (inflation-adjusted). Analysis of current platform data indicates this figure has increased more than tenfold to $4.66 (WordStream Market Report, 2023). In particularly competitive sectors such as legal services, insurance, and financial products, high-intent search terms regularly command rates exceeding $54.00 per click (SEMRush Keyword Analytics, 2024).

This cost inflation has significant implications for market structure. The U.S. Small Business Administration defines small businesses as those with fewer than 500 employees—a category encompassing 99.9% of all American businesses (SBA Office of Advocacy, 2023). Given that these enterprises typically operate with limited marketing budgets, the escalating cost of digital customer acquisition has effectively marginalized their ability to compete for visibility in the digital marketplace.

Compounding this economic disadvantage, major digital platforms employ sophisticated tracking mechanisms—including pixel-based audience modeling and cross-site profiling—that create data asymmetries between large and small advertisers. Platform algorithms ostensibly designed to maximize “relevance” frequently amplify these disparities through preferential treatment of entities with larger historical datasets and spending capacity (Journal of Marketing Research, “Algorithmic Bias in Digital Advertising,” 2022).

Addressing Common Counterarguments

Proponents of the current regulatory landscape often argue that digital advertising’s rise reflects its inherent superiority rather than regulatory asymmetry. They point to precision targeting, real-time measurement, and conversion optimization as technological advantages that justify higher costs and market concentration. However, this perspective overlooks how these “efficiencies” often manifest primarily for enterprises with substantial data assets and marketing budgets. Recent research published in the International Journal of Advertising demonstrates that customer acquisition costs for small businesses have increased 312% since 2015, while conversion rates have declined by 22% during the same period (Morgan & Chen, 2023).

Some might contend that telemarketing’s decline simply represents inevitable technological evolution rather than regulatory distortion. While technological advancement certainly plays a role, examination of adjacent channels suggests otherwise. Email marketing—governed by the comparatively flexible CAN-SPAM Act—has maintained relatively stable costs despite similar technological transformation. According to industry analysis, email marketing costs approximately $12 per new customer acquisition compared to $56 for search advertising and $75 for social media advertising (Digital Marketing Institute, 2023).

Join Substack

Asymmetrical Regulatory Frameworks and Their Market Distortion Effects

While telemarketing could theoretically provide an alternative channel for small business customer acquisition, the current regulatory environment imposes disproportionate compliance burdens on entities with limited administrative resources.

The Telephone Consumer Protection Act (TCPA) and National Do-Not-Call Registry: Economic Impacts

The Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 (47 U.S.C. § 227) established a complex regulatory framework that has expanded significantly through subsequent rulemaking. Among its provisions:

- Calls to mobile telephones require documented prior express consent, despite the fact that mobile lines now constitute 75.2% of all telephone subscriptions in the United States (FCC Communications Marketplace Report, 2023).

- Access to the federal Do-Not-Call registry requires payment of $80 per area code (with the first five free), creating a maximum potential annual cost of $22,038 for businesses operating nationally (FTC DNC Registry Access Fee Notice, 2023).

- Thirty states and hundreds of municipalities maintain separate Do-Not-Call registries with independent fee structures, multiplying compliance costs (American Teleservices Association Compliance Survey, 2022).

- The FCC’s own compliance guidance acknowledges that TCPA record-keeping requirements consume approximately 103.2 staff hours annually for the average business (FCC DA-23-478A1, 2023).

- The Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy estimates that telemarketing regulations account for 19.7% of all regulatory compliance costs for firms with fewer than 20 employees (SBA Regulatory Impact Analysis, 2022).

Regulatory Asymmetry as a Market Structuring Mechanism

This regulatory framework creates a self-reinforcing cycle with significant implications for market structure. As compliance costs increase, legitimate small businesses abandon telephone marketing channels. Large corporations can either absorb potential penalties as a cost of doing business or redirect marketing expenditures toward digital advertising platforms. Meanwhile, fraudulent operators simply ignore regulatory requirements entirely, creating a selection bias wherein legitimate businesses are disproportionately burdened.

The FCC’s enforcement data supports this analysis: over 73% of TCPA enforcement actions between 2018-2023 targeted legitimate businesses for technical violations rather than fraud operations (FCC Enforcement Bureau Annual Report, 2023). This enforcement pattern accelerates the exodus of compliant businesses from the channel while having minimal impact on actual telecommunications fraud.

The Litigation Externality

A particularly troubling consequence of the current regulatory regime is the emergence of what telecommunications industry analysts term “lawsuit mills”—law firms specializing in identifying technical TCPA violations and initiating class action litigation. In March 2024, settlement documents from Rodriguez v. Aerocare Holdings revealed attorney fees of $1.28 million—approximately 86.5% of the total settlement—for a case involving technical consent documentation failures rather than substantive consumer harm (TCPA World Case Analysis, 2024).

Lobbying Expenditures and Regulatory Capture in Communications Policy

Digital advertising platforms are not merely passive beneficiaries of telecommunications regulatory policy—they actively participate in its formation through significant lobbying expenditures and regulatory engagement. In 2020, Google allocated $20.1 million and Meta $21.3 million toward U.S. federal lobbying activities (OpenSecrets.org Lobbying Database, 2021).

Both organizations have submitted formal comments to Federal Communications Commission proceedings regarding telecommunications regulations. In CG Docket No. 02-278, Google advocated for “stricter robocall penalties” while simultaneously proposing a STIR/SHAKEN authentication safe harbor to “reduce abusive calls while preserving legitimate communications” (Google Comments, DA 20-160A1 ¶ 42). Similarly, Meta’s Ex Parte filing emphasized the importance of “robust enforcement mechanisms against illegitimate callers” while advocating for “balanced approaches that recognize legitimate business communication” (Meta Ex Parte Comment, 5, 2021).

The economic implications of this policy influence are substantial. Americans reportedly lost approximately $40 billion to telephone-based fraud schemes in 2022 (Truecaller Insights Report, 2022), while U.S. businesses directed over $212 billion toward digital advertising platforms during the same period (eMarketer Digital Ad Spending Report, 2023). Regulatory agencies frequently cite fraud statistics to justify increasingly stringent telecommunications rules, creating a feedback loop that channels marketing expenditures toward digital platforms.

The Consumer Protection Question

The most persuasive defense of strict telemarketing regulations centers on consumer protection benefits. Indeed, unwanted calls have measurably declined following TCPA enforcement actions, with Americans reporting 31% fewer unwanted calls in 2022 compared to 2018 (FTC Consumer Sentinel Network, 2023). However, this reduction must be weighed against significant economic costs—particularly for emerging businesses without established customer bases.

More importantly, evidence suggests current enforcement patterns focus disproportionately on technical violations by legitimate businesses rather than actual fraud operations. The Association of Corporate Counsel notes that 76% of recent TCPA settlements involved documentation technicalities rather than substantive consumer harm (ACC Regulatory Compliance Survey, 2023). This pattern suggests that reformed enforcement priorities could maintain consumer protection benefits while reducing barriers to market entry.

Defenders of the status quo might argue that telemarketing creates uniquely disruptive consumer experiences that justify asymmetrical regulation. Yet recent neuropsychological research indicates that digital advertising’s constant presence creates measurable cognitive load and attention fragmentation effects that potentially exceed the momentary disruption of a telephone call (Journal of Consumer Psychology, “Attention Economics in Digital Environments,” 2022). Additionally, digital platforms’ extensive data collection practices raise privacy concerns that match or exceed those associated with telemarketing.

Technological Alternatives to Restrictive Regulation

Contemporary telecommunications technology offers sophisticated authentication mechanisms that could substantively address consumer protection concerns without imposing prohibitive compliance burdens on legitimate businesses:

STIR/SHAKEN Authentication Protocols

The STIR (Secure Telephone Identity Revisited) and SHAKEN (Signature-based Handling of Asserted information using toKENs) protocols leverage cryptographic authentication to verify a call’s true origin—effectively preventing caller ID spoofing, where malicious actors falsify numbers to deceive recipients. These protocols have been fully implemented by all major carriers as of June 2021 (FCC STIR/SHAKEN Implementation Report, 2022).

Branded Caller ID (BCID) Systems

Building upon the STIR/SHAKEN foundation, Branded Caller ID technologies register and display authenticated organizational identities, providing recipients with immediate visual confirmation of legitimate callers. Although BCID adoption remains in early stages—approximately 17.3% of eligible businesses have implemented compatible systems—initial data indicates consumer trust improvements of 68% for authenticated calls (First Orion Consumer Trust Survey, 2023).

Constitutional Considerations and Legal Precedent

The current telecommunications regulatory framework raises significant constitutional questions regarding commercial speech protections. In Barr v. American Association of Political Consultants (2020), the Supreme Court struck down the government-debt exception to the TCPA on First Amendment grounds, with Justice Kavanaugh writing that content-based restrictions on speech must satisfy strict scrutiny. Similarly, in ACA International v. Federal Communications Commission (2018), the D.C. Circuit vacated portions of the FCC’s 2015 TCPA Order, emphasizing that overly broad interpretations of “automatic telephone dialing system” risk infringing protected speech.

Legal scholars have noted that the current regulatory regime may be vulnerable to further constitutional challenges. As Professor Eugene Volokh observed in the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology: “Commercial speech regulations that effectively preclude entire channels of communication without narrowly tailored exceptions raise serious First Amendment concerns, particularly when technological alternatives exist” (Volokh, “First Amendment Constraints on Anti-Robocall Legislation,” 2021).

Policy Recommendations for Regulatory Reform

Based on the preceding analysis, this paper proposes the following regulatory modifications to balance consumer protection with market competition concerns:

- De Minimis Exemption: Implement a volumetric threshold exempting businesses placing low to modest number of outbound calls per month from certain TCPA documentation requirements, similar to the approach taken in securities regulation under SEC Rule 501 (Regulation D).

- Authentication Safe Harbor: Establish a rebuttable presumption of compliance for calls utilizing authenticated Branded Caller ID systems, following the model established by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) for qualifying electronic health record systems.

- Do-Not-Call Fee Structure Reform: Eliminate registry access fees for businesses with documented compliance programs, maintaining fees only for entities with previous violations.

- Risk-Based Enforcement Allocation: Redirect enforcement resources toward actual fraud operations rather than technical violations by compliant businesses, applying the risk-based regulatory approach advocated by the Office of Management and Budget Circular A-4.

- Tiered Consent Framework: Develop a graduated compliance regime that scales documentation requirements proportionally to call volume, consistent with the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act’s mandate for tiered regulatory structures.

Beyond Government Intervention

Some industry representatives suggest that self-regulation rather than statutory reform would better address these market distortions. While industry-led initiatives like the Communications Fraud Control Association have introduced promising authentication protocols, historical evidence suggests self-regulation proves most effective when backstopped by balanced government frameworks. The Interactive Advertising Bureau’s self-regulatory initiatives, for instance, have failed to prevent digital advertising cost inflation or market concentration, demonstrating the limitations of industry-only approaches in highly concentrated markets (Competition Policy International, 2023).

Rather than viewing telecommunications regulation through a binary lens of “more” versus “less,” policymakers should pursue targeted reforms that maintain core consumer protections while reducing compliance burdens that disproportionately impact emerging businesses. The policy recommendations outlined above represent a balanced approach that acknowledges both legitimate consumer protection concerns and the importance of maintaining diverse marketing channels for businesses of all sizes.

Conclusion: From “Don’t Be Evil” to Digital Dominance

1994 was an exciting time to be at MCI. Vint Cerf, widely known as one of the “Fathers of the Internet,” had just rejoined the company as Senior Vice President, and MCI started selling digital interconnections to the backbone of the Internet to businesses. This put me at the intersection of two worlds—traditional cold calling and the dawn of the commercial internet.

The 1990s internet had a distinctly frontier-like feeling. There was a palpable sense of wonder and experimentation that’s hard to fully convey to those who didn’t experience it firsthand. The early web was characterized by techno-optimism—a belief that the internet would democratize information, connect humanity, and solve major world problems. My wife used to wear a pin that read “The Meek Shall Inherit the Earth”—a sentiment that perfectly captured the egalitarian promise of this emerging digital landscape.

This optimism was embodied in Google’s original motto “Don’t be evil,” which promised a more ethical approach to business. The early Google culture prioritized users over profits. This was exemplified in 2010 when Google stopped cooperating with Chinese government censorship on search results, sacrificing access to that market to make a stand on free speech, though this stance would later change. Yet today, we’ve witnessed Google’s transformation from a user-focused search engine to an advertising behemoth that dominates global digital advertising.

The irony is striking: regulatory frameworks ostensibly designed to protect consumers from telemarketing’s intrusions have inadvertently concentrated power in the hands of digital platforms whose market dominance raises equally significant concerns about privacy, competition, and accessibility. “Don’t be evil” has given way to “Pay to participate”—with participation fees beyond the reach of most entrepreneurs.

As we navigate this pivotal moment in communications policy, we must recognize that healthy markets require accessible pathways for businesses of all sizes to reach potential customers. The technological optimism that characterized the early internet needn’t be abandoned—but it must be channeled toward regulatory frameworks that foster competition rather than concentration. Only then can we reclaim some measure of that original promise: an open digital economy where innovation isn’t confined to those with the deepest pockets.

Methodology and Data Sources

This analysis synthesizes data from multiple governmental and industry sources, including FCC and FTC regulatory dockets, Securities and Exchange Commission filings, industry association surveys, and academic research. Digital advertising cost data was derived from platform transparency reports and marketing analytics firms. Telecommunications regulatory impact assessments were compiled from Small Business Administration reports, FCC compliance guidance, and federal court records.

Limitations include the proprietary nature of certain digital advertising algorithms and the difficulty of precisely quantifying regulatory compliance costs across diverse business models. Future research should address these limitations through expanded empirical studies of small business marketing channel selection and regulatory impact assessments.

References

American Express. (1965). Annual Report. American Express Company

Archives.American Teleservices Association. (2022). Compliance Survey. ATA Research

Division.Direct Marketing Association. (1986). Annual Statistical Fact Book. DMA

Publications.Direct Marketing Association. (1988). Cost Benchmark Report. DMA Publications.

Direct Marketing Association. (2002). Statistical Fact Book. DMA Publications.

Equitable Trust Company. (1908). Annual Report. Banking History Archives.

Federal Communications Commission. (2023). Communications Marketplace Report. FCC.

Federal Communications Commission. (2023). Enforcement Bureau Annual Report. FCC.

Federal Communications Commission. (2022). STIR/SHAKEN Implementation Report. FCC.

Federal Communications Commission. (2023). Compliance Guidance Document DA-23-478A1. FCC.

Federal Trade Commission. (2023). DNC Registry Access Fee Notice. FTC.

First Orion. (2023). Consumer Trust Survey. First Orion Research.

Google. (2021). Comments, DA 20-160A1. FCC Docket CG 02-278.

Journal of Marketing Research. (2022). “Algorithmic Bias in Digital Advertising.” American Marketing Association.

Magellan Solutions. (2023). Industry Survey Report. Magellan Analytics.

Meta. (2021). Ex Parte Comment. FCC Docket CG 02-278.

Midwest Steel Co. (1936). Company Bulletin. Industrial Archives Collection.

OpenSecrets.org. (2021). Lobbying Database. Center for Responsive Politics.

SEMRush. (2024). Keyword Analytics Report. SEMRush.

Small Business Administration. (2022). Regulatory Impact Analysis. SBA Office of Advocacy.

Small Business Administration. (2023). Small Business Profile. SBA Office of Advocacy.

TCPA World. (2024). Case Analysis: Rodriguez v. Aerocare Holdings. TCPA World Legal Analysis.

Time Inc. (1957). Annual Report. Time Inc. Corporate Archives.

Truecaller. (2022). Insights Report: Phone Scams. Truecaller Research.

Volokh, E. (2021). “First Amendment Constraints on Anti-Robocall Legislation.” Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, 34(2), 498-537.

WordStream. (2023). Market Report. WordStream Analytics.