The perspectives in this article are personal and do not represent the positions of any companies with which the author is associated.

Introduction

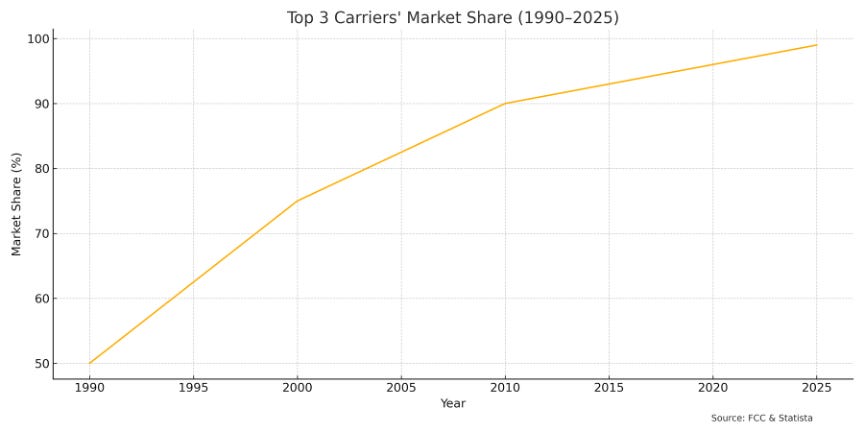

Regulatory frameworks supposedly designed to spur competition have enabled a wireless oligopoly to emerge. Despite the promise of the 1996 Telecom Act and dramatic cost-cutting technology advances, three carriers now control 99% of the U.S. market. As a result, today’s American consumers pay among the highest prices in the developed world for wireless services.

The concept of regulatory capture—wherein regulatory bodies come to serve the interests of the industries they oversee rather than the public—is hardly new in American economic discourse. Yet its manifestations across different sectors exhibit striking parallels that reveal broader patterns of how market power is manufactured and maintained through seemingly neutral governance structures. This article, the first in a series examining regulatory capture in the telecommunications sector, has evolved from a competitive landscape following the Telecommunications Act of 1996 to today’s entrenched oligopoly dominated by Verizon, AT&T, and T-Mobile.

These “Big Three” carriers collectively control approximately 99% of the U.S. wireless market as of 2023 (Statista, 2024). This extraordinary concentration contradicts the standard economic narrative that technological advancement naturally produces more competitive markets. Despite dramatic technological improvements that have slashed the underlying costs of service provision, research confirms that Americans pay some of the highest rates for mobile service among developed economies, with North America being the most expensive region for mobile data globally, averaging $4.98 per GB compared to the global average of $3.12 (Statista, 2024).

This anomaly invites scrutiny: How has such market concentration persisted despite regulatory frameworks ostensibly designed to foster competition? The answer lies in examining the structural and regulatory asymmetries that have enabled dominant carriers to entrench their positions while systematically putting smaller competitors at a disadvantage. Through analysis of industry practices, regulatory frameworks, and enforcement patterns, this article demonstrates how ostensibly neutral mechanisms for consumer protection and industry governance have functionally operated as tools for concentrating market power and erecting barriers to entry.

Regulatory Asymmetry in Telecommunications

Neutral-sounding rules burden small carriers much more than big ones. What once drove competition and slashed wholesale rates by 90% has flipped—large incumbents now use those same rules to crush smaller rivals.

The telecommunications market failure stems from structural biases in governance mechanisms that systematically advantage dominant players while creating burdens for smaller competitors.

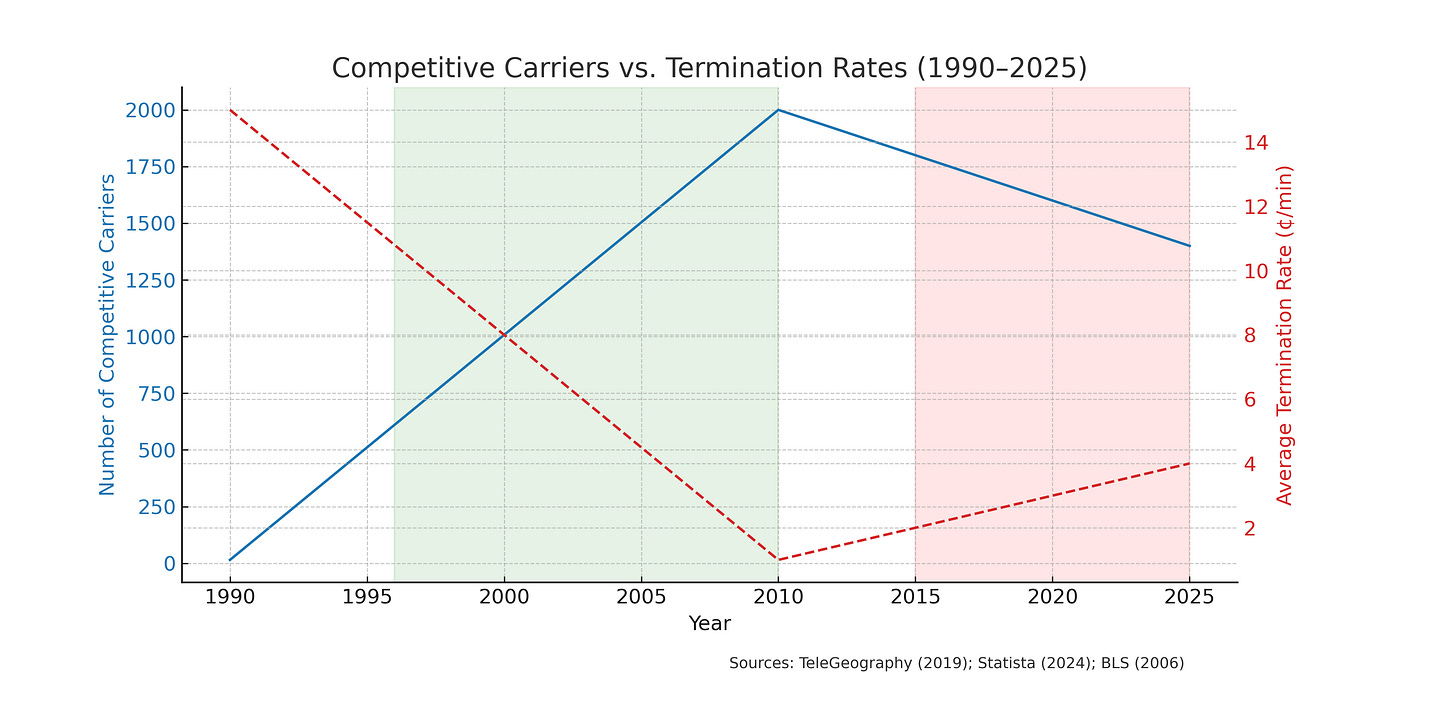

This concentration has dramatically reduced the number of competitive carriers operating in the telecommunications marketplace. The consolidation began in voice services but has extended to text messaging and mobile data, as the same three dominant carriers control the infrastructure for all three services. This cross-sector dominance is critical to understanding the full scope of market power: a consumer seeking mobile data service must generally purchase it from the same limited set of carriers that control voice and messaging. This integration of services has made it increasingly difficult for competitive local exchange carriers (CLECs) and landline providers to compete as consumers shift to bundled mobile services.

To understand this impact, it’s essential to grasp how the wholesale telecom market functions. Wholesale telecommunications refers to the bulk sale of telecom services and network capacity between carriers. Larger network operators sell access to smaller providers. These smaller providers lack their own comprehensive infrastructure. In this ecosystem, “intermediate carriers” are companies that facilitate the connection between originating and terminating carriers, essentially acting as middlemen in the call routing process. They purchase minutes and connectivity in bulk from major carriers and resell this capacity to smaller operators, creating a complex web of interconnections.

Despite the prevailing view among large carriers that intermediate carriers merely erode margins without adding value, these middlemen have historically served as critical market makers that increase competition and drive down prices. Following the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the proliferation of intermediate carriers helped reduce wholesale voice rates by over 90% in less than a decade. As the number of competitive carriers grew from fewer than 20 in the early 1990s to over 2,000 by 2010, average wholesale termination rates plummeted from approximately 15 cents per minute to less than a penny, with the cost savings being passed on to end users. However, as market consolidation has accelerated since 2015, these gains have stagnated and even begun to reverse in certain market segments, demonstrating the concrete economic impact of reduced competition.

At the heart of this market failure lies a framework of regulatory asymmetry—structural biases in governance mechanisms that systematically advantage dominant players while creating disproportionate burdens for smaller competitors. These asymmetries operate through several key mechanisms. First, fixed compliance costs imposed equally on all market participants hamper smaller providers who must allocate a significantly larger percentage of their revenue to compliance. Second, technical standards and interconnection requirements often incorporate specifications that benefit scale and existing infrastructure, functioning as de facto gatekeepers that protect incumbent positions. Third, self-regulatory bodies, while ostensibly neutral, frequently reflect the interests of their largest members, who can shape enforcement priorities and technical standards to consolidate their advantage.

The Industry Traceback Group: The Power Behind the Curtain

The Industry Traceback Group is controlled by the largest carriers and operates like a pay-to-play organization that sets enforcement priorities. Its tiered membership discourages smaller providers from speaking up, resulting in enforcement outcomes that favor the incumbents.

Perhaps no organization better exemplifies how self-regulatory bodies can function as mechanisms for reinforcing market dominance than the Industry Traceback Group (ITG). Established in 2015 and administered by USTelecom, the ITG is presented as a collaborative effort to combat illegal robocalls and protect consumers (USTelecom, 2020). However, examination of its governance structure and operating procedures reveals a more complex reality. The organization’s leadership and decision-making processes are dominated by representatives from major carriers, while smaller providers have limited representation and influence.

It is important to understand that while the ITG is not itself an enforcement agency, it wields tremendous influence by providing information and recommendations to actual enforcement entities including the FCC and state Attorneys General. This information-sharing function creates a powerful leverage point in the regulatory ecosystem that can shape enforcement priorities and outcomes.

The ITG’s tiered membership structure further reveals this power imbalance: AT&T, Comcast, T-Mobile, and Verizon serve as “platinum partners,” while Bell, Charter, Cox, and Lumen operate as “gold partners,” and companies like Consolidated, Sinch, Twilio, US Cellular, and Windstream participate as “silver partners.” Each tier requires escalating membership fees, effectively creating a pay-to-influence system where the largest carriers with the deepest pockets secure the most significant roles in governance and policy-setting.

A concerning aspect of this regulatory ecosystem is the pervasive culture of silence it engenders among telecommunications providers. Many companies—particularly smaller ones most vulnerable to enforcement actions—are fearful of making public criticisms of the ITG or any regulators, or even issuing public statements in their own defense, for fear of regulatory reprisal. This chilling effect on open industry discourse further insulates the regulatory apparatus from scrutiny and accountability, allowing problematic enforcement patterns to continue unchallenged. The silence is particularly troubling given that these entities ostensibly exist to serve the public interest rather than to operate as unquestionable authorities.

The enforcement patterns facilitated by ITG data show a systematic bias: smaller providers face more aggressive scrutiny and enforcement actions, while the major carriers that constitute the organization’s leadership enjoy greater leniency when similar compliance issues arise on their networks. Analysis of traceback data reveals that when problematic traffic is identified on smaller carriers’ networks, it is frequently traced only to that point before enforcement is initiated, whereas similar traffic on major carriers’ networks is more likely to be pursued further upstream to identify the true originator.

Join Substack

All Access Telecom: The Attorneys General Task Force Shoots First, Questions Later

When 51 state Attorneys General publicly warned All Access Telecom—without prior notice or due process—they flagged a small carrier while ignoring larger upstream sources of the same traffic. This case exemplifies how raw ITG data becomes political ammunition against vulnerable rivals, with no accountability for mistaken accusations.

The problematic dynamics of the current enforcement system were clearly illustrated in the April 2025 case of All Access Telecom, which received a public warning letter from 51 state Attorneys General without any prior opportunity to respond. In his reply, CEO Lamar Carter noted that All Access had not been contacted by any U.S. regulators in over 15 months prior to this public action, despite maintaining a robust compliance program including prompt responses to traceback requests, complete Know-Your-Customer documentation, and full implementation across their network (Carter, 2025).

Most tellingly, Carter identified that much of the suspect traffic referenced in the Attorneys General letter originated from several large upstream providers “among the most prominent in the U.S. telecom ecosystem”—yet none of these major carriers were referenced in the public notice, despite being the actual source of the flagged calls. All Access was one of eight carriers that received this warning letter, but was the only company to issue a public response. Whether the silence from the other seven companies represents an admission of guilt or simply a strategic choice to avoid antagonizing a powerful coalition of state attorneys with effectively unlimited legal resources remains unknown, highlighting the chilling effect of the current regulatory structure.

The coordination between regulatory bodies further compounds this asymmetry. The state Attorneys General Task Force specifically cited ITG traceback data as justification for their enforcement action against All Access, demonstrating how information flows between the FCC, ITG, and state enforcement entities function as a closed system that operates without procedural safeguards (North Carolina Department of Justice, 2025). This interdependent enforcement apparatus proceeds with no due process mechanisms or presumption of innocence for smaller carriers caught in its machinery. As Carter noted in his response, despite reviewing seven recent quarterly FCC traceback reports, All Access had not been flagged as either an originator or point-of-entry provider in any of them—raising questions about the evidentiary basis for such coordinated public enforcement actions.

Notably, neither the Task Force nor any of the 51 Attorneys General ever responded publicly to Carter’s detailed refutation, nor did they acknowledge or apologize for potential reputational harm caused by their public accusations. This pattern of public accusation followed by silence when challenged is not unique to All Access; conversations with executives at numerous other telecommunications companies reveal similar experiences, with many choosing to simply absorb the reputational damage rather than risk further regulatory attention through a public defense.

The Enforcement Disparity

Fifty-one state Attorneys General issued a public warning to All Access Telecom—with no notice or chance to respond—while overlooking larger upstream carriers responsible for the same traffic. This case shows how unverified ITG data can be used as political leverage against smaller operators, without any accountability for errors.

Independent analysis of enforcement patterns conducted over a five-year period (2020-2025) reveals compelling evidence of a significant disparity in regulatory treatment based on carrier size. Smaller telecommunications providers with less than 1% market share were approximately four times more likely to receive warning letters or enforcement actions for suspected illegal traffic compared to major carriers (Mondaq, 2021).

This disparity extends beyond frequency to include procedural differences as well. When faced with compliance issues, smaller providers typically receive notices demanding resolution within 48-72 hours before facing potential service interruption. In contrast, documentation obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests shows that major carriers routinely receive extended remediation periods of up to 30 days for similar infractions, along with opportunities for multiple compliance extensions not offered to smaller operators. These procedural differences create a fundamentally unequal enforcement environment despite ostensibly uniform regulatory requirements.

The “gateway provider” designation—intended to address fraud and spam originating from overseas—has further exacerbated these regulatory asymmetries. While ostensibly neutral, this regulatory classification has made selling to international service providers substantially riskier for smaller operators who lack the legal and compliance resources to navigate the additional scrutiny. Many smaller carriers, including All Access, have responded by abandoning international markets entirely, effectively ceding this business to dominant carriers who can absorb the compliance costs. This represents a structural reconfiguration of the market through regulatory mechanisms that disproportionately impact smaller providers.

The irony is twofold: first, rather than directly confronting overseas bad actors, regulators have essentially deputized carriers as enforcement agents; second, despite the ITG’s stated purpose of tracing call origins, enforcement predominantly targets accessible intermediaries rather than actual originators when jurisdictional challenges arise. As Carter aptly analogized in his response letter, blaming an intermediate carrier for call content is like “citing a city’s recycling truck driver for transporting hazardous waste” rather than addressing the resident who improperly disposed of it (Carter, 2025).

Telnyx: The “Regulation by Enforcement” Problem

The FCC’s multimillion-dollar fine against Telnyx shows how vague “know-your-customer” expectations can be weaponized—imposed by enforcement actions rather than clear rules.

Telnyx’s recent confrontation with the FCC further illustrates how enforcement mechanisms can be weaponized against smaller providers. In February 2025, the FCC proposed a $4.5 million fine against Telnyx for allegedly failing to prevent a government impersonation robocall scheme that specifically targeted FCC staff and their families (FCC, 2025). Despite Telnyx identifying the suspicious account during routine monitoring, terminating it within hours, and voluntarily reporting the incident to the FCC that same day, the Commission proceeded with a substantial fine. Most troublingly, Telnyx only transmitted 1,117 completed calls from this bad actor before shutting it down—a minuscule fraction compared to the billions of illegal robocalls that flood networks monthly with limited enforcement response.

In its formal response, Telnyx directly challenged the FCC’s action as a violation of Executive Order 13892, “Promoting the Rule of Law Through Transparency and Fairness in Civil Administrative Enforcement and Adjudication,” which explicitly prohibits “regulation by enforcement” (Telnyx, 2025). The order requires agencies to “avoid unfair surprise” and apply “only standards of conduct that have been publicly stated in a manner that would not cause unfair surprise” (Executive Order 13892, 2019). Telnyx argued that the FCC was attempting to enforce vague “know-your-customer” standards that had never been clearly defined in formal regulations—effectively creating new compliance requirements through enforcement rather than through proper rulemaking procedures.

This argument is particularly compelling because the FCC has never established clear, objective standards for customer vetting procedures. With no specific guidance on data collection requirements or verification protocols, carriers are forced to guess what might satisfy regulatory expectations—a situation that creates both fear and inefficiency. This intentionally ambiguous regulatory environment allows enforcement agencies maximum subjective flexibility, leading carriers to either implement costly over-reactions or risk insufficient compliance measures. The end result is a process that becomes inherently political rather than procedurally fair, with smaller carriers at a systematic disadvantage.

The company’s position highlighted how regulatory agencies can leverage ambiguous standards selectively against smaller providers, who lack the resources to challenge such actions, while providing larger carriers with the flexibility of unclear requirements that can be navigated through superior legal resources and political connections. This pattern of “regulation by enforcement” creates persistent uncertainty for smaller market participants while allowing dominant carriers to operate with greater predictability through their influence over the regulatory process itself.

The recent Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals decision vacating a $57 million FCC fine against AT&T further underscores the constitutional infirmities in this regulatory structure. The court ruled that the FCC’s in-house enforcement proceedings violate Seventh Amendment rights to jury trials in civil penalty cases—a conclusion that directly impacts the Telnyx case and casts doubt on the entire enforcement apparatus (CommLaw Group, 2025). Even within the FCC itself, Commissioner Simington dissented from the Telnyx penalty precisely because he believed the Supreme Court’s Jarkesy precedent rendered such administrative penalties unconstitutional (Wiley, 2025).

This constitutional challenge strikes at the heart of the regulatory imbalance: the FCC’s administrative enforcement process effectively denies regulated entities their constitutional right to have penalties determined by a jury of their peers in an Article III court. Instead, these civil penalties—which can reach millions of dollars—are imposed through in-house administrative law proceedings where the FCC acts simultaneously as prosecutor, judge, and jury. While larger carriers with extensive resources can often challenge these determinations all the way to federal appellate courts (as AT&T successfully did), smaller providers typically lack the financial capacity to mount such comprehensive legal challenges, further cementing the enforcement disparity.

The resource asymmetry is stark: federal and state government agencies operate with effectively unlimited legal budgets for enforcement actions, while targeted providers—especially smaller ones—face ruinous legal costs even when successfully defending themselves. This disparity creates a powerful incentive for smaller providers to settle cases regardless of merit, simply because the financial burden of mounting a proper legal defense often exceeds the proposed penalties. Even in cases where a provider might prevail on the legal merits, the reputational damage from a prolonged, public regulatory battle can devastate a telecommunications business whose customers demand regulatory certainty. This fundamental resource imbalance transforms the enforcement process itself into a powerful market-shaping mechanism that inherently favors dominant incumbents over smaller competitors.

These cases demonstrate how industry-led governance structures, operating in concert with regulatory bodies of questionable constitutional authority, create asymmetric enforcement patterns that disadvantage competitive carriers while consolidating incumbent advantage.

Structural Solutions and Technological Fixes

Tools like STIR/SHAKEN and traceback protocols already exist to block fraud without restricting market entry. What’s needed now is a transparent standards and objective compliance benchmarks that protect consumers while preserving genuine competition.

The enforcement disparity is particularly vexing given that technological solutions for addressing illegal traffic already exist. The combination of STIR/SHAKEN authentication protocols and ITG traceback capabilities has made identifying bad actors relatively straightforward.

STIR/SHAKEN is a framework of technical protocols and implementation procedures designed to combat illegal caller ID spoofing on public telephone networks. STIR (Secure Telephony Identity Revisited) is the technology that verifies the calling number through digital certificates, while SHAKEN (Signature-based Handling of Asserted Information using toKENs) is the framework for implementing STIR within carrier networks. Together, they enable service providers to authenticate and verify caller ID information for voice calls, helping to reduce fraudulent robocalls and scams.

Illegal call spoofing occurs when callers deliberately falsify the information transmitted to caller ID displays to disguise their identity with the intent to defraud, cause harm, or wrongfully obtain something of value. Under the Truth in Caller ID Act, the FCC prohibits such misleading or inaccurate caller ID information, with penalties of up to $10,000 per violation.

Despite these tools, the true challenge lies not in detection but in structural limitations of the regulatory framework itself. The FCC’s own registration process for obtaining FRN numbers and 499ID credentials—prerequisites for operating in the U.S. market—lacks meaningful verification standards or procedural safeguards. Any entity, including international companies with limited U.S. presence, can obtain these credentials through simple online applications with minimal scrutiny.

This creates a regulatory paradox: while enforcement disproportionately burdens legitimate smaller carriers with extensive compliance requirements, the actual entry points for problematic traffic remain virtually unrestricted. A more balanced approach would establish reasonable entry requirements that prevent fly-by-night operations without creating insurmountable barriers for legitimate competitive carriers.

True consumer protection requires both technological solutions and structural reforms that address the root causes of market dysfunction rather than symptoms. Authentication mechanisms like STIR/SHAKEN demonstrate that technical solutions can address issues like call spoofing and fraud without restricting market entry or advantaging scale. Branded Caller ID and similar innovations illustrate how transparency-focused solutions can empower consumer choice rather than restricting provider access. A consumer-centric approach would focus on establishing clear, technically-neutral standards that apply equally to all providers regardless of size or market position.

Enforcement Agencies Playing Chess While Fraudsters Play Checkers

Fraudsters play whack-a-mole; smaller carriers get left holding the bag. Today’s system penalizes cooperative operators while the real bad actors slip away. Granting safe harbors to good-faith providers and focusing enforcement on true offenders would protect consumers.

The telecommunications industry faces a fundamental challenge: communications networks inherently attract fraud and abuse, particularly with the rise of VoIP and SIP technologies that make geography increasingly irrelevant for bad actors. Yet current enforcement strategies often target cooperative service providers rather than the perpetrators themselves, creating a misalignment of incentives that ultimately undermines effective consumer protection.

Service providers who implement robust compliance programs, respond promptly to traceback requests, and actively monitor their networks should be viewed as partners in combating fraud—not as convenient targets for regulatory action. The current enforcement approach, which frequently penalizes well-meaning service providers while actual fraudsters remain elusive, may generate positive press but fails to address the root problem. Like a game of whack-a-mole, fraudsters simply migrate to the next exploitable carrier, rendering individual enforcement actions largely ineffective at systemic change.

This reality is evidenced by the fact that even the largest and most sophisticated telecommunications companies have fallen victim to cyber attacks and network exploitation. Carriers like AT&T and Bandwidth.com, despite their substantial resources and advanced security measures, have experienced significant breaches—demonstrating that vulnerability to abuse is not necessarily a reflection of negligence or insufficient compliance efforts.

What service providers need is regulatory clarity, not regulatory ambiguity. As telecommunications business operators, carriers require specific, actionable guidance on: (1) precisely what customer vetting procedures they must implement to ensure their networks aren’t used for harm, and (2) what ongoing monitoring practices will satisfy regulatory expectations. Without such clarity, carriers must either over-invest in elaborate compliance systems or risk becoming enforcement targets—with smaller providers disproportionately disadvantaged by this uncertainty.

The current system also creates perverse incentives where carriers feel compelled to pay substantial membership fees to industry associations or retain politically-connected legal counsel simply to reduce their chances of becoming enforcement targets. This dynamic functions as an unofficial tax on market participation that disproportionately burdens smaller providers and further consolidates market power among dominant carriers.

A truly effective regulatory framework would focus enforcement efforts on actual bad actors while establishing clear, objective compliance standards for service providers. Carriers who demonstrate good-faith compliance with these standards should receive safe harbor protections, encouraging cooperation rather than adversarial relationships between industry and regulators. Such an approach would better serve both consumer protection goals and competitive market functioning than the current system of selective enforcement and regulatory ambiguity.

Conclusion

Today’s telecom oligopoly isn’t the result of fair competition—it’s built on uneven rules and industry-run oversight that shut out newcomers.

The telecommunications market in the United States demonstrates how regulatory asymmetries can function as powerful mechanisms for concentrating market power and erecting barriers to competitive entry. Through differential enforcement burdens, strategic control of network access, and industry-dominated governance structures, dominant carriers have effectively engineered a market structure that protects their position while constraining competitive threats.

The consequences extend far beyond telecommunications itself. The concentration of power in essential communications infrastructure affects innovation, economic opportunity, and consumer welfare across the economy. As communications technologies become increasingly central to economic and civic participation, the costs of market dysfunction in this sector ripple throughout society.

In subsequent articles in this series, we will examine other examples of regulatory capture and market collusion in the telecommunications industry.

Through careful examination of these patterns across different sectors, a clearer picture emerges of how regulatory capture functions in our industry— through subtle structural biases that systematically advantage incumbents while disadvantaging new entrants. Recognizing these patterns is the first step toward developing more effective governance mechanisms that can foster genuine competition while protecting legitimate public interests in the digital age.

Find me on https://www.linkedin.com/in/noahkamrat/ or on Substack.